L’oncologie française met les bretelles, la ceinture et boutonne la braguette.

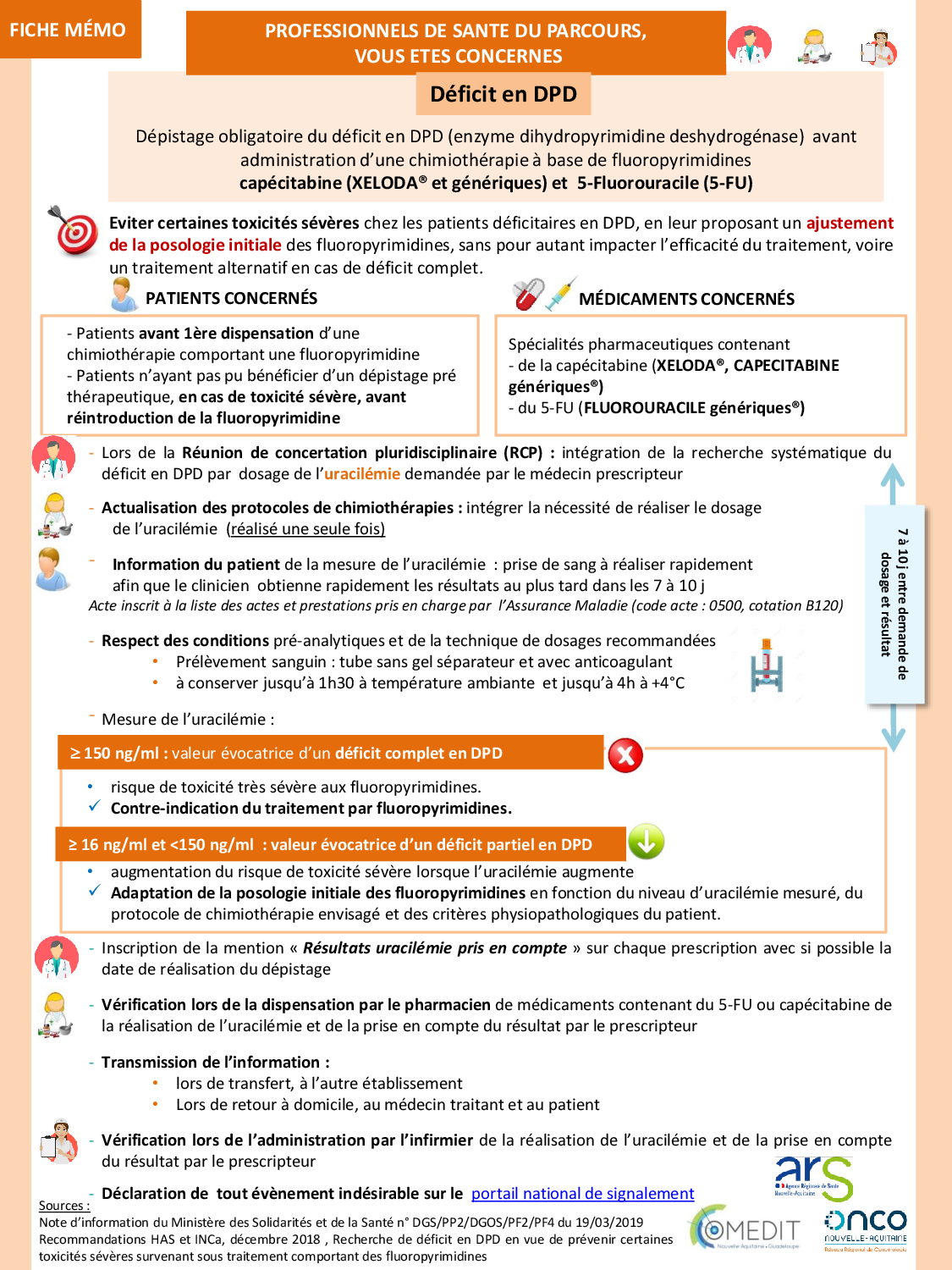

Pendant 20 ans le milieu de la cancérologie française, dans sa grande majorité, a refusé de prendre en compte le déficit en DPD, maintenant la vérification de l’absence de déficit doit être faite par l’oncologue, le pharmacien, l’infirmière, le médecin traitant et le patient. Ce n’est pas notre association qui va s’en plaindre.